Monthly Nature Book Reviews by Pat Biliter

|

And the 2008 winner of the Burroughs Medal was …….

The Fragile Edge, Diving and Other Adventures in the South Pacific, by Julia Whitty, marine biologist, conservationist, expert SCUBA diver, famed documentary filmmaker, award-winning author, and tireless champion of the South Pacific coral reefs and their astonishingly diverse wildlife. Almost every page of this book is filled with vividly described imagery of perhaps the most colorful and complex ecosystems on earth. So why is it so depressing to read? For us northeastern Ohioans, landlocked far from any saltwater, the reef-fringed atolls of the south Pacific Ocean seem like hopelessly remote places that we will never have a chance to see. Even for those who can afford to get there, the air trip can be a two-day ordeal with multiple changes into ever more rickety aircraft. Therein lies their vulnerability. The global mindset about South Pacific atolls is that thanks to their tiny area, remoteness, and small human populations, these miniscule islands are suitable only for high-speed resource exploitation and are not worthy of protection. Half of the world’s coral reefs have already died, with the rest unlikely to last beyond 2050. This means that the 4,000 species of fish (20 percent of all fish species on earth) that depend on them to complete their life cycles, not to mention nearly a million other marine species, are destined to disappear as well. Charles Darwin explored Pacific atolls on his historic round-the-world cruise on the HMS Beagle. Frankly, they bewildered him. How did some 330 of these tiny, low-lying, sandy islets form in the middle of the vast, 2-1/2-mile-deep Pacific Ocean, hundreds, if not thousands, of miles from any land or other source of sediment? Thanks to the development of sonar and powerful subsurface imaging geophysical instruments, we now know that each atoll marks the spot of a long-collapsed, 10,000-to-12,000-foot-high volcano that subsided back into the sea, leaving no trace other than a circular band of coral reefs and sandy coral sediments that once encircled the volcano. Polynesians refer to the enclosed lagoons as the “navel” of the long-vanished volcano. Julia Whitty Astonishing beauty and diversity of a tropical reef Polynesian people say that that God lives in the lagoon, not the sky. Typical South Pacific atoll, surrounded by coral reefs - Although admittedly beautiful and biologically diverse, are these bits of land good for anything to the rest of the world? They lack the coal, oil, timber, metallic ores, gold, and vast agricultural lands that have made so many continental countries wealthy. Their small populations are masters at fishing, ocean canoeing, and surviving on tiny patches of land, but they are relatively poor in material goods compared to people in developed countries, not to mention that the native inhabitants are not white, which would have been viewed as a major demerit back in the 1940s and 1950s, when France and the United States decided to use remote Pacific atolls for nuclear testing. During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States detonated 66 nuclear bombs in the region, 23 on Bikini Atoll and 43 on Enewetak Atoll. Between 1963 to 1996, France detonated 200 nuclear bombs in their coral reef test range. The native population was forcibly evacuated from their ancestral homeland. Others on nearby atolls were advised not to eat fish or coconuts due to nuclear contamination, two foods that were stables of the island diet. The amount of radiation exceeded calculations, so that almost the entire human population in the region suffered the effects of radioactive fallout. These included some of the highest leukemia rates in the world, especially among infants, children, and teenagers. Even worse were the so-called “jellyfish babies”, human children born without legs, arms, or head that could only survive a minute or two after birth. Native people have never been compensated for the loss of their homeland, deaths, or damage to their health. Nuclear testing has since been banned, although radiation still lingers on land, in sea water, and absorbed in plant and marine life. The remaining atolls and their coral reefs remain vulnerable due to other environmental threats. The delicate corals build their shells out of calcium carbonate, a material that dissolves readily in acid. As carbon dioxide has built up in the atmosphere, the oceans have absorbed large amounts of the gas, which reacts with seawater to form carbonic acid, in turn dissolving the shells of corals, clams, scallops, oysters, and other shellfish. Coral reefs are also highly temperature dependent, and if seawater temperature rises above 86 degrees F, all corals will die. The low-lying islands are also vulnerable to sea-level rise. The final blow is world-wide overfishing of the reefs, usually with destructive methods like dynamite. Bottom line: the future of these awe-inspiring ecosystems looks bleak. By Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President pbiliter@hotmail.com |

And the 2012 winner of the Burroughs Medal was …….

|

Sex and the River Styx by Edward Hoagland. Hailed as the ‘Henry David Thoreau of the Modern Age’, Hoagland has authored 24 best-selling books and hundreds of magazine articles. Literary critics view him as America’s greatest essayist of the past century. So why was it so hard for me to understand—much less enjoy—a book honored by the John Burroughs Association?

The volume consists of 13 loosely connected, semi-autobiographical essays spanning the author’s lifetime, from a shy teenager to a famous man in his 70s. He takes the reader through his sexual fantasies, his work with the Barnum and Baily and Ringling Brothers Circus, two failed marriages, relief work in east Africa, travels to remote parts of southern Asia, and the aches and pains of getting old (in some of the best non-medical writing on the male aging process in American literature). So what does any of this have to do with natural history? It took a second reading for me to grasp the powerful conservation message subtly expressed in his book, coupled with a better understanding of the author himself. His greatest burden in life was a chronic and severe stutter that deeply affected his life choices. Painfully shy, he withdrew from people at an early age to find solace in the company of animals and nature. After all, animals never make fun of stutterers. His disability affected his relationship with women, as well as his choice of a career. A self-taught expert in natural history who could have easily excelled in the sciences, he chose to major in literature and humanities at Harvard University instead. Words were extremely important to him, but his difficulty in verbally expressing himself propelled him toward a career in writing. But he never lost his love of wildlife. As a freshman and sophomore at Harvard in 1951 and 1952, he spent his summers travelling with the Barnum and Bailey and Ringling Brothers circus, where he had signed up as a “cage boy,” a laborer in charge of tending to the circus animals. The job entailed 16-hour workdays, 7 days a week, for $2 a day plus room and board with the circus. But that didn’t count wondrous perks like having a giraffe lick salt from his face, or the giant hippo that loved having his gums massaged…..a great way for a stutterer to show off in front of pretty girls that he would have dreaded talking to. Edward Hoagland Living conditions of circus animals But the author spends as much time describing the people who work at the circus as he does the animals. Suddenly he was in the company of drifters, loners, ex-cons, and alcoholics, all performing brutal physical labor for low wages. He describes handsome, muscular young men with the hats pulled low over their eyes, men who knew how to hop on a moving freight train without saying good-bye to anyone, in other words, men who would be any potential mother-in-law’s nightmare. Even the clowns were not what they seemed. Clowns who had brought delight, laughter, and joy to untold thousands of children across the county, had themselves abandoned their own wives and children, choosing to cut all contact with their own families. In two essays, the author takes us into rarely visited parts of northeastern India and Tibet. We explore an incredibly rugged area occupied by some 26 indigenous tribes, long feared by lowland Indians due to their warlike culture and cannibalistic rituals. But even here, wildlife is disappearing. Young men were once expected to kill a tiger as an entry into manhood, and to proudly wear its jawbone on formal occasions. But the tigers are all gone, and so are the leopards that replaced them for ritualistic purposes. The focus is now on small Himalayan wildcats, as we humans slaughter our way down the cat family for wearing apparel. The author made some nine extended trips to East Africa over the decades, attracted by the amazing wildlife of the African plains. What he found instead was a downward spiral of chaos, starvation, disease, civil war, outlaw warlords, tribal and religious hatred, and a complete breakdown of civil authority. This led to the collateral damage of shattered herds of wildlife that once filled the plain. He regrets that all the species that he once cared for as a teenager “cage boy” working for the circus—tigers, hippos, rhinos, elephants—have all become critically endangered outside of zoos. It all happened in the course of one man’s lifetime, and no one saw it coming. The author was one of the first to sound the alarm that by destroying nature, we are cutting our own feet out from under us. The environmental crises we now face—climate change, ground water depletion, overfishing, soil loss, long term drought—are no longer just about protecting plants and animals. A new species could soon be added to the list of threatened species: Homo sapiens. By Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President, pbiliter@hotmail.com Circus laborers, known as “roustabouts” Tawang Monastery in Arunchal Pradesh Rwandan genocide |

2020 Burroughs Medal Winner

Great naturalists come in a variety of flavors. E.O. Wilson is a scientific naturalist; John James Audubon was an artistic naturalist; Aldo Leopold was an outdoorsman’s naturalist; and Rachel Carson was a conservation naturalist. But John Burroughs was above all a literary naturalist. It seems quite appropriate that the John Burroughs Association has presented an award for the finest example of natural history writing every year since 1926.

The winner of the 2020 Burroughs Medal is Entangled, People and Ecological Change in Alaska’s Kachemak Bay, by Marilyn Sigman. After having studied biology at Stanford University and zoology at the University of Alaska, she dedicated her career to educating children and adults about the obscure science of ecology, but not in classrooms. She preferred to do her teaching in the forests, in the mountains, and on the beaches of Alaska.

When our BNC president, Yvette Slusarski, first asked me to research this year’s Burroughs medal winner and to write a “book report” for our members, I was excited to do it. That is, until I found the title of the 2020 winner, which seemed too specific to a faraway place to be of much interest to folks living in northeast Ohio.

I was wrong. This beautifully written volume imparts a powerful conservation message that applies just as much to the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Chesapeake Bay as it does to Alaska’s Kachemak Bay. Her prose reminds me of Rachel Carson’s writing--richly scientific while being almost poetic at the same time. After reading her book, I’m ready to rush off to Homer, Alaska (aka, “The End of the Road”), to personally experience the natural marvels and beauty that she so eloquently describes in her book.

Yet behind all the beauty is a tragic history. One of the most biologically diverse and economically bountiful ecosystems on earth has been decimated by the human tendency to take more from nature than we want to give back. What archeologists and anthropologists have learned is that humans are prone to settle down, to over-populate, and then to over-harvest their surrounding resources.

The result is a kind of historical amnesia about the natural world. The author refers to it as “shifting baseline syndrome.” The world around us is changing so quickly that what we modern humans think of as “natural” is nothing like the nature experienced by our grandfathers, and their view of nature was starkly different from their parents and grandparents.

The author describes the fascinating history of human exploitation of numerous species in the bay, but due to space constraints, I’ll limit myself to one creature, arguably the cutest mammal on earth, the Pacific sea otter.

These animals are guilty of two great sins. First, as keystone predators they prefer eating the same animals that we enjoy eating----clams, oysters, crabs, abalone and scallops. And after catching their prey on the sea bottom, they have the gall to bring it to the surface and eat it in plain view of human fisherman and crabbers who are after the same prey. Second, sea otters grow the most luxurious fur coat of any mammal on earth, with over 1,000,000 hairs per square inch. They once ranged across 6,000 miles from Baja California northward to the Aleutians and westward to Japan. By the early 1900s they were on the cusp of extinction, with their range and population reduced by over 99 % by fur hunters. By then all the otters in Kachemak Bay were gone.

Therein lies the problem: a collapsing food web. Otters eat sea urchins, and sea urchins eat kelp. If you take away the otters, the sea urchins (a single individual can live to be two hundred years old) will reproduce by the millions, decimating the kelp at the base of the food web.

Like beads falling off a string, the loss of the kelp, coupled with over-harvesting by humans, led to extirpation of one species after the next in the bay—green sea urchins, sea cucumbers, gumboot chitons, sockeye salmon, king salmon, herring, oysters, clams, scallops, yellowfin sole, rock sole, Dungeness crab, Tanner crab, harbor seals, and king crab by the millions. Homer, Alaska, is still billed as the Halibut Fishing Capital of the World, but the days of catching 400-pound halibut in the bay are gone forever. Most halibut caught today are known as “chickens,” 10 pounds or less.

I found the author’s conclusions a bit disturbing. She dedicates the book and her love of nature to her father, “who took me fishing” as a little girl growing up in Montana. Now in her 60s, following a lifetime of impassioned conservation and teaching others to appreciate nature, she acknowledges that the only constant in nature is change. Change is inevitable, and now it is being intensified and accelerated by human activities. Our only recourse is to enjoy whatever is left of the natural world, and to appreciate and mourn the bit-by-bit that disappears forever over time.

My brothers and I also learned to love nature from our father, who took us on hundreds of fishing and hunting trips as we were growing up, often in places where today it is no longer possible to hunt and fish due to habitat loss and pollution. I suspect the reason that the author’s conclusion bothers me is that, deep down inside, I know that she is right.

-- Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President

The winner of the 2020 Burroughs Medal is Entangled, People and Ecological Change in Alaska’s Kachemak Bay, by Marilyn Sigman. After having studied biology at Stanford University and zoology at the University of Alaska, she dedicated her career to educating children and adults about the obscure science of ecology, but not in classrooms. She preferred to do her teaching in the forests, in the mountains, and on the beaches of Alaska.

When our BNC president, Yvette Slusarski, first asked me to research this year’s Burroughs medal winner and to write a “book report” for our members, I was excited to do it. That is, until I found the title of the 2020 winner, which seemed too specific to a faraway place to be of much interest to folks living in northeast Ohio.

I was wrong. This beautifully written volume imparts a powerful conservation message that applies just as much to the Great Lakes, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Chesapeake Bay as it does to Alaska’s Kachemak Bay. Her prose reminds me of Rachel Carson’s writing--richly scientific while being almost poetic at the same time. After reading her book, I’m ready to rush off to Homer, Alaska (aka, “The End of the Road”), to personally experience the natural marvels and beauty that she so eloquently describes in her book.

Yet behind all the beauty is a tragic history. One of the most biologically diverse and economically bountiful ecosystems on earth has been decimated by the human tendency to take more from nature than we want to give back. What archeologists and anthropologists have learned is that humans are prone to settle down, to over-populate, and then to over-harvest their surrounding resources.

The result is a kind of historical amnesia about the natural world. The author refers to it as “shifting baseline syndrome.” The world around us is changing so quickly that what we modern humans think of as “natural” is nothing like the nature experienced by our grandfathers, and their view of nature was starkly different from their parents and grandparents.

The author describes the fascinating history of human exploitation of numerous species in the bay, but due to space constraints, I’ll limit myself to one creature, arguably the cutest mammal on earth, the Pacific sea otter.

These animals are guilty of two great sins. First, as keystone predators they prefer eating the same animals that we enjoy eating----clams, oysters, crabs, abalone and scallops. And after catching their prey on the sea bottom, they have the gall to bring it to the surface and eat it in plain view of human fisherman and crabbers who are after the same prey. Second, sea otters grow the most luxurious fur coat of any mammal on earth, with over 1,000,000 hairs per square inch. They once ranged across 6,000 miles from Baja California northward to the Aleutians and westward to Japan. By the early 1900s they were on the cusp of extinction, with their range and population reduced by over 99 % by fur hunters. By then all the otters in Kachemak Bay were gone.

Therein lies the problem: a collapsing food web. Otters eat sea urchins, and sea urchins eat kelp. If you take away the otters, the sea urchins (a single individual can live to be two hundred years old) will reproduce by the millions, decimating the kelp at the base of the food web.

Like beads falling off a string, the loss of the kelp, coupled with over-harvesting by humans, led to extirpation of one species after the next in the bay—green sea urchins, sea cucumbers, gumboot chitons, sockeye salmon, king salmon, herring, oysters, clams, scallops, yellowfin sole, rock sole, Dungeness crab, Tanner crab, harbor seals, and king crab by the millions. Homer, Alaska, is still billed as the Halibut Fishing Capital of the World, but the days of catching 400-pound halibut in the bay are gone forever. Most halibut caught today are known as “chickens,” 10 pounds or less.

I found the author’s conclusions a bit disturbing. She dedicates the book and her love of nature to her father, “who took me fishing” as a little girl growing up in Montana. Now in her 60s, following a lifetime of impassioned conservation and teaching others to appreciate nature, she acknowledges that the only constant in nature is change. Change is inevitable, and now it is being intensified and accelerated by human activities. Our only recourse is to enjoy whatever is left of the natural world, and to appreciate and mourn the bit-by-bit that disappears forever over time.

My brothers and I also learned to love nature from our father, who took us on hundreds of fishing and hunting trips as we were growing up, often in places where today it is no longer possible to hunt and fish due to habitat loss and pollution. I suspect the reason that the author’s conclusion bothers me is that, deep down inside, I know that she is right.

-- Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President

And the 2011 winner of the Burroughs Medal was …….

….The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey, an acclaimed essayist, short story writer, award-winning author, and passionate nature lover, especially the meadows and forests of her native Maine.

When I first saw the title, I assumed that it must be a clever allegorical reference to some other topic. After all, do snails even make noise when they eat, and does anyone bother to listen to them? Not likely. But I was wrong on both counts. The title is literally about listening to a snail eating, although couched in the tragic circumstances of the author’s devastating illness that changed her life forever.

The tragedy began with what should have been the trip of a lifetime, a visit to a small Swiss village. Toward the end of her vacation, she began suffering from flu-like symptoms, which evolved into extreme weakness, dizziness, exhaustion, and the inability to sit or stand without fainting. Her trip back to Maine was a blur, and she is still doesn’t know how she managed to pack her suitcase, take taxi rides, and process in and out of airports to get back to her Maine farmstead from Switzerland. All she remembers is that she was very, very sick.

Puzzled at first, her doctors eventually diagnosed her ailment as autoimmune dysautononmia. It causes your body’s automatic nervous system to stop functioning, affecting breathing, heartbeat, digestion, balance, and temperature control.

This was followed by a diagnosis of mitochondria disease. Mitochondria occur by the thousands in every cell of our bodies. They control how we turn nutrients and oxygen into energy. Once they stop functioning, the victim suffers extreme exhaustion even after the mildest of activities, such as turning the pages of a book. There is no cure for either condition. The victim either gets better or dies. In the author’s case, it took almost two decades to recover, including spending months staring helplessly at the ceiling, unable to move her body.

The author’s pre-sickness life had been filled with friends, family, work, sailing, gardening, and woodland hikes with her beloved dog Brandy. Now it was all over, and she found herself becoming more and more cut off from the world, while her healthy friends moved on with their lives, families, and careers. She had become a ghost, or at least a ghost of her former self. Unable to move, she was now a horizontal person, and none of the things she once loved---offices, stores, galleries, libraries, and movie theaters---are designed to accommodate horizontal people.

One day a friend tried to cheer her up with a terracotta pot of field violets dug from a lawn. On her way to the author’s sickroom, she noticed a two-inch-long land snail crawling on the forest floor, and on a whim, placed it into the pot with the violets. The author was grateful for her friend’s thoughtfulness, but worried about the welfare of a snail pulled out of its environment and then confined to a flowerpot perched on a wooden crate next to her bed. Given her debilitated condition,

Elisabeth Tova Bailey

Common eastern land snail, Neohelix albolabris

-

she had no idea how she could take care of it or even keep it in the pot (eventually upgraded to a terrarium). All she could do was watch it, an activity that ultimately saved her own life.

Just inches from the author’s head, the snail spent the nights exploring the flowerpot, the underlying overflow dish, and the supporting crate, traveling almost to the floor. By day the nocturnal animal tucked into its shell and fall asleep in a little hollow that it had made in the soil beneath the violet leaves. To feed it, the author started leaving wilted flower petals in the overflow dish, because the snail refused to touch the living blooms on the plant. Woodland snails are detritivores, preferring to eat decaying vegetation. Its favorite food turned out to be portabella mushrooms from the refrigerator, which it devoured.

Thanks to its rasp-like tongue, the snail was a noisy eater. In the deep still of the night, the author could hear the diminutive and comforting sound of the snail’s radula rasping against its food. The author imagined a tiny person munching on even tinier celery stalks. A snail’s tongue, called a radula, contains 2,640 teeth, arranged in 80 rows of 33 each. The teeth are replaced with new rows as they wear down, eliciting the author’s admiration for a species that had evolved teeth replacement, as opposed to a species that had evolved the dental profession.

As the months went by, the snail became more and more a comfort and a cherished companion. Watching another animal living its life a few inches from her head was soothing and relaxing. The readiness of the snail go about its life despite a drastic change in its environment somehow gave purpose to the author’s own life. If life mattered to the snail, it should matter to her. It led her out of a dark time during the first year of her illness into a world beyond her own species.

Eventually the worst of the author’s negative fantasies came to pass. Her snail was missing, nowhere to be found. Where could it be? She tried not to think of the dreaded crunch of a caretaker, friend or family member walking into her room without seeing the snail on the floor. It was at this point that author realized how much she loved the little animal, which she treasured as much than her own tenuous life. Happily, a friend finally located the snail. It had burrowed under the moss of the terrarium to lay and to tend to a clutch of eggs that resulted in 118 baby snails crawling all over the terrarium (land snails are hermaphroditic, and can self-fertilize). Her malacologist friends (scientists who study snails) assert that the author is the first human in history to ever record a snail tending to its own eggs. Scientists had always assumed that a snail revisiting its clutch would be more likely to eat the eggs than take care of them.

Her friends encouraged her to put her experience and thoughts about the snail down on paper. It turned out to be a laborious process. It took her four years to complete the 170 pages of this small book. But it culminated in a volume that has become required reading in grade schools, high schools, universities, nursing schools and medical schools around the world, a book that within a year of publication had garnered the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing, the Outdoor Book Award in Natural History, and the John Burroughs Medal. Not bad for a first attempt at writing a book. By Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President, pbiliter@hotmail.com

Photomicrogaph of the surface of a snail’s tongue, or radula, a Latin word meaning “scraper”

When I first saw the title, I assumed that it must be a clever allegorical reference to some other topic. After all, do snails even make noise when they eat, and does anyone bother to listen to them? Not likely. But I was wrong on both counts. The title is literally about listening to a snail eating, although couched in the tragic circumstances of the author’s devastating illness that changed her life forever.

The tragedy began with what should have been the trip of a lifetime, a visit to a small Swiss village. Toward the end of her vacation, she began suffering from flu-like symptoms, which evolved into extreme weakness, dizziness, exhaustion, and the inability to sit or stand without fainting. Her trip back to Maine was a blur, and she is still doesn’t know how she managed to pack her suitcase, take taxi rides, and process in and out of airports to get back to her Maine farmstead from Switzerland. All she remembers is that she was very, very sick.

Puzzled at first, her doctors eventually diagnosed her ailment as autoimmune dysautononmia. It causes your body’s automatic nervous system to stop functioning, affecting breathing, heartbeat, digestion, balance, and temperature control.

This was followed by a diagnosis of mitochondria disease. Mitochondria occur by the thousands in every cell of our bodies. They control how we turn nutrients and oxygen into energy. Once they stop functioning, the victim suffers extreme exhaustion even after the mildest of activities, such as turning the pages of a book. There is no cure for either condition. The victim either gets better or dies. In the author’s case, it took almost two decades to recover, including spending months staring helplessly at the ceiling, unable to move her body.

The author’s pre-sickness life had been filled with friends, family, work, sailing, gardening, and woodland hikes with her beloved dog Brandy. Now it was all over, and she found herself becoming more and more cut off from the world, while her healthy friends moved on with their lives, families, and careers. She had become a ghost, or at least a ghost of her former self. Unable to move, she was now a horizontal person, and none of the things she once loved---offices, stores, galleries, libraries, and movie theaters---are designed to accommodate horizontal people.

One day a friend tried to cheer her up with a terracotta pot of field violets dug from a lawn. On her way to the author’s sickroom, she noticed a two-inch-long land snail crawling on the forest floor, and on a whim, placed it into the pot with the violets. The author was grateful for her friend’s thoughtfulness, but worried about the welfare of a snail pulled out of its environment and then confined to a flowerpot perched on a wooden crate next to her bed. Given her debilitated condition,

Elisabeth Tova Bailey

Common eastern land snail, Neohelix albolabris

-

she had no idea how she could take care of it or even keep it in the pot (eventually upgraded to a terrarium). All she could do was watch it, an activity that ultimately saved her own life.

Just inches from the author’s head, the snail spent the nights exploring the flowerpot, the underlying overflow dish, and the supporting crate, traveling almost to the floor. By day the nocturnal animal tucked into its shell and fall asleep in a little hollow that it had made in the soil beneath the violet leaves. To feed it, the author started leaving wilted flower petals in the overflow dish, because the snail refused to touch the living blooms on the plant. Woodland snails are detritivores, preferring to eat decaying vegetation. Its favorite food turned out to be portabella mushrooms from the refrigerator, which it devoured.

Thanks to its rasp-like tongue, the snail was a noisy eater. In the deep still of the night, the author could hear the diminutive and comforting sound of the snail’s radula rasping against its food. The author imagined a tiny person munching on even tinier celery stalks. A snail’s tongue, called a radula, contains 2,640 teeth, arranged in 80 rows of 33 each. The teeth are replaced with new rows as they wear down, eliciting the author’s admiration for a species that had evolved teeth replacement, as opposed to a species that had evolved the dental profession.

As the months went by, the snail became more and more a comfort and a cherished companion. Watching another animal living its life a few inches from her head was soothing and relaxing. The readiness of the snail go about its life despite a drastic change in its environment somehow gave purpose to the author’s own life. If life mattered to the snail, it should matter to her. It led her out of a dark time during the first year of her illness into a world beyond her own species.

Eventually the worst of the author’s negative fantasies came to pass. Her snail was missing, nowhere to be found. Where could it be? She tried not to think of the dreaded crunch of a caretaker, friend or family member walking into her room without seeing the snail on the floor. It was at this point that author realized how much she loved the little animal, which she treasured as much than her own tenuous life. Happily, a friend finally located the snail. It had burrowed under the moss of the terrarium to lay and to tend to a clutch of eggs that resulted in 118 baby snails crawling all over the terrarium (land snails are hermaphroditic, and can self-fertilize). Her malacologist friends (scientists who study snails) assert that the author is the first human in history to ever record a snail tending to its own eggs. Scientists had always assumed that a snail revisiting its clutch would be more likely to eat the eggs than take care of them.

Her friends encouraged her to put her experience and thoughts about the snail down on paper. It turned out to be a laborious process. It took her four years to complete the 170 pages of this small book. But it culminated in a volume that has become required reading in grade schools, high schools, universities, nursing schools and medical schools around the world, a book that within a year of publication had garnered the William Saroyan International Prize for Writing, the Outdoor Book Award in Natural History, and the John Burroughs Medal. Not bad for a first attempt at writing a book. By Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President, pbiliter@hotmail.com

Photomicrogaph of the surface of a snail’s tongue, or radula, a Latin word meaning “scraper”

And the 2014 winner of the Burroughs Medal was…

The author grew up as an unambitious, day-dreaming schoolgirl who achieved decidedly unremarkable scores on her university entrance exams, prompting her mother’s threat to enroll her in secretarial college instead. The thought of that possibility sparked a sudden attitude change toward her academic studies. She entered the University of Edinburgh, where she majored in philosophy and quickly developed a reputation as a brilliant student. She published her first volume of poetry at the age of 20. Today she is a professor of creative writing at the University of Stirling in her native Scotland.

Sightlines is not a continuous narrative but rather a series of essays, many about the harsh landscapes of her beloved Scotland. The author has lots of friends in interesting places, doing interesting things. Pathologists, ornithologists, ship captains, archeologists, botanists, and museum curators populate her book. All are keen on sharing what they do with her, and often invite her to participate in their activities.

Sightlines is not a continuous narrative but rather a series of essays, many about the harsh landscapes of her beloved Scotland. The author has lots of friends in interesting places, doing interesting things. Pathologists, ornithologists, ship captains, archeologists, botanists, and museum curators populate her book. All are keen on sharing what they do with her, and often invite her to participate in their activities.

The author’s “sightlines” can occur at any scale. They include (1) straining to hear the whoosh and whistle of the shimmering Aurora Borealis amid the biting cold and utter silence of a Greenland fjord at night, (2) a centimeter-by-centimeter excavation of the grave of a Bronze Age woman who died 5,000 years ago, (3) cleaning whale skeletons in the great hall of a Norwegian natural history museum, or even (4) microscopically exploring thin sections of cancerous human organ tissues.

Getting invited to a morgue for a guided tour of diseased human tissue may not sound like a fun outing to most of us, but the author somehow makes the experience seem eerie and exciting. I especially liked her observation that if you were challenged to design and build “a pump, or a gas-exchange system, or a nutrient absorbing device, you would never, ever, think of using meat” to build it.

Getting invited to a morgue for a guided tour of diseased human tissue may not sound like a fun outing to most of us, but the author somehow makes the experience seem eerie and exciting. I especially liked her observation that if you were challenged to design and build “a pump, or a gas-exchange system, or a nutrient absorbing device, you would never, ever, think of using meat” to build it.

|

This is how a poet summarizes the evolutionary history of animal anatomy. Everything we are and everything we do emerges from our simply being “meat.”

The author is not a scientist, but it soon becomes obvious that she knows a great deal about the landforms, archeology, marine mammals, birds, and wildflowers of the British Isles. One of her great passions are whales. She explores the brutal history of these amazing animals at the hands of humans. The bodies of at least a million whales of all species literally went up in smoke to fuel the table lamps and streetlamps of the 19th Century. |

|

Most of us picture a beach vacation as relaxing on a tropical white sand beach shaded by coconut palms and fringed by a calm, blue sea. The author prefers the chilly, windswept, foggy, rainy, and wave-battered coastlines of remote uninhabited islands in the North Atlantic. She is fascinated by their ever-changing patterns of sunlight and shadow reflected from the rough seas, cloudy skies, and barren rocky outcrops that surround her.

Despite her vulnerability to terrible sea sickness, she convinces captains of small vessels to take her to remote, uninhabited, protected islands like St. Kilda and Rona, where she and her friends spend weeks cataloging archeological sites, breeding birds, and rare plants. |

Especially poignant was the remote Scottish island of Rona, settled by Gaelic people many centuries ago. In 1695 victims of a shipwreck crawled on shore, grateful for the chance to get aid from a nearby village. But all the villagers were found dead. In fact, the entire island population had died of unknown causes. While building a boat to rescue themselves, the shipwreck survivors buried all the remains they could find, marking each grave with a nameless Celtic stone cross. Today, despite the island’s remoteness and protected status, the 300-year-old crosses are steadily being stolen by vandals visiting the island without a permit.

There are great poets who cannot write good prose, and great prose authors who cannot write poetry. But Kathleen Jamie, like Edgar Allan Poe, excels at both. She has helped create a relatively new genre, “landscape writing,” contrasting with the more familiar “natural history writing.” Her vivid descriptions of the sights, sounds, smells, and feel of her settings literally pull the reader into her scenes. Reading her book, you feel as though you were standing at her side.

By Pat Biliter, former Burroughs Nature Club vice-president, pbiliter@hotmail.com

There are great poets who cannot write good prose, and great prose authors who cannot write poetry. But Kathleen Jamie, like Edgar Allan Poe, excels at both. She has helped create a relatively new genre, “landscape writing,” contrasting with the more familiar “natural history writing.” Her vivid descriptions of the sights, sounds, smells, and feel of her settings literally pull the reader into her scenes. Reading her book, you feel as though you were standing at her side.

By Pat Biliter, former Burroughs Nature Club vice-president, pbiliter@hotmail.com

*****

2022 February Selection: Dominion of Bears, by Sherry Simpson

Dominion of Bears, by Sherry Simpson, biologist, journalist, reporter, bear aficionado, lifelong nature nut, professor of creative writing at the University of Alaska, as well as one of Alaska’s most accomplished essayists. Born and raised in Alaska, she died suddenly in 2020 due to an inoperable brain tumor, to the shock of legions of her fans, her adoring students, and all who knew and loved her.

At first glance, her book seems a bit daunting: 436 pages covering everything you ever wanted to know about brown, black, and polar bears. She spent 10 years researching and writing her masterpiece, as evidenced by the 102-page bibliography at the end of book. But this isn’t so much a book about the biology of bears (although rich in bear data) as it is the story of how humans have reacted to bears across time.

Ancient peoples viewed bears with far more respect than we do, not because of their fearsome size and strength, but because they reminded them of humans. Traits such as keen intelligence, omnivorous diet, flat-footed gait, and human-like posture when sitting, standing, and walking convinced them that bears were our closest relatives in the animal world, if not our direct ancestors.

To modern humans the presence of bears is the very definition of wilderness. To save wild bears for posterity means protecting large tracts of pristine habitat needed to support them. Bears are not just an apex predator; they are an umbrella species. Maintaining a healthy bear population simultaneously provides prime habitat for thousands of other species of plants and animals that share their space.

Before reading this book, I always assumed that Alaskans were proud of living in America’s last wild frontier in close proximity to bears. Sadly, that’s not true. Many Alaskan politicians and their supporters view local wildlife as little more than a potential monetary resource. Alaska is one of the last places on earth where trophy hunters can still find large wild animals to kill. Businessmen from the Lower 49 will eagerly exchange their ties and suit coats for hunting gear and pay a wilderness guide up to $25,000 a week for a chance to kill a bear, caribou, or moose.

Urged by politicians (at great cost to state taxpayers), Alaskan wildlife agencies have been shooting thousands of wolves and bears from helicopters for years. The plan is to eradicate predators from designated tracts of the Alaskan wilderness, justified as an “experiment” to increase the population of big herbivores for hunters, many of whom travel to Alaska from out-of-state to spend lots of money.

The author struggles to explain why some men have such an urge to shoot small holes into big animals (as John Muir described it), creatures that they neither need nor plan to eat. Does it somehow make

Professor Sherry Simpson (1960 – 2020)

Alaskan brown bear, Ursos arctos

them more “manly?” The Hollywood myth of Davy Crockett fending off a snarling bear armed only with a Bowie knife does not apply here. Trophy hunters typically shoot bears using high-powered rifles and 8X scopes from at least 100 yards away, while the bear is happily munching on a pile of stale Krispy Kreme doughnuts left at a bait station by their hunting guide (perfectly legal in Alaska). No guide wants his deep-pocketed client to go back home disappointed and empty-handed.

What if you unexpectedly encounter a bear in the wild? What do you do? The answer can be complicated, as the author makes clear. It depends on what species of bear you encounter and on what it is doing at the time. Much of the advice out there is simply wrong.

Advice #1: Drop your backpack and run away. The bear will be distracted by the food in the backpack, allowing you to make your escape. Analysis: Bad plan. This is a great way to train bears to threaten people. Alaskan bears have learned to make mock charges at salmon fishermen, knowing that they’ll run away and abandon their coolers full of fish for them to eat.

Advice # 2: Lie down, curl up, and play dead. Analysis: Bad plan. This might work for grizzlies, who attack only when they feel threatened. Just hope that the grizzly doesn’t decide to make sure that you’re dead. In contrast, black bears regard anyone playing dead as an easy opportunity for a meal.

Advice # 3: If you see a black bear, stand tall, spread out your coat or jacket, try to look larger, speak loudly, or bang pots together to make a racket. If you have a companion, stand close together to look larger to the bear. Back up slowly. Do not turn and run away. Analysis: Good plan. Black bears are great bluffers. They are prone to make mock charges, and to snort and stamp the ground to try to get you to leave their space. They rarely attack. On the other hand, if a black bear is creeping up on you from behind, in total silence, staring intently, you are now on the menu. Be prepared for the worst.

Advice # 4: Carry a gun or a can of bear spray. Analysis: A toss-up. Statistics show that people who carry guns are just as likely to get killed or injured as those who carry bear spray, and people who fail to discharge either weapon are no more likely to get killed or injured than those that do. In the panic of the moment, people either can’t find the can, or fail to disengage the safety on the gun, or just plain miss the target.

Bottom line: Far more Alaskans have been killed by domestic dogs and moose than by bears. Park rangers swear that preventing human/bear conflicts is more about controlling human behavior than bear behavior. People are careless with food and garbage; they assume that bears enjoy posing with you in a selfie; or they approach those cute bear cubs while mamma bear is standing there, watching.

A sad chapter of the book recounts the plight of the polar bear. Polar bears that once swam 25 miles to reach the southern end of the Arctic ice pack now have to swim 150 miles and more to reach their summer feeding grounds. They arrive exhausted and emaciated. The entire population is slowly starving to death. A few more decades of climate change, and the only surviving polar bears will be in zoos. By Pat Biliter, former Burroughs Nature Club vice-president, pbiliter@hotmail.com

At first glance, her book seems a bit daunting: 436 pages covering everything you ever wanted to know about brown, black, and polar bears. She spent 10 years researching and writing her masterpiece, as evidenced by the 102-page bibliography at the end of book. But this isn’t so much a book about the biology of bears (although rich in bear data) as it is the story of how humans have reacted to bears across time.

Ancient peoples viewed bears with far more respect than we do, not because of their fearsome size and strength, but because they reminded them of humans. Traits such as keen intelligence, omnivorous diet, flat-footed gait, and human-like posture when sitting, standing, and walking convinced them that bears were our closest relatives in the animal world, if not our direct ancestors.

To modern humans the presence of bears is the very definition of wilderness. To save wild bears for posterity means protecting large tracts of pristine habitat needed to support them. Bears are not just an apex predator; they are an umbrella species. Maintaining a healthy bear population simultaneously provides prime habitat for thousands of other species of plants and animals that share their space.

Before reading this book, I always assumed that Alaskans were proud of living in America’s last wild frontier in close proximity to bears. Sadly, that’s not true. Many Alaskan politicians and their supporters view local wildlife as little more than a potential monetary resource. Alaska is one of the last places on earth where trophy hunters can still find large wild animals to kill. Businessmen from the Lower 49 will eagerly exchange their ties and suit coats for hunting gear and pay a wilderness guide up to $25,000 a week for a chance to kill a bear, caribou, or moose.

Urged by politicians (at great cost to state taxpayers), Alaskan wildlife agencies have been shooting thousands of wolves and bears from helicopters for years. The plan is to eradicate predators from designated tracts of the Alaskan wilderness, justified as an “experiment” to increase the population of big herbivores for hunters, many of whom travel to Alaska from out-of-state to spend lots of money.

The author struggles to explain why some men have such an urge to shoot small holes into big animals (as John Muir described it), creatures that they neither need nor plan to eat. Does it somehow make

Professor Sherry Simpson (1960 – 2020)

Alaskan brown bear, Ursos arctos

them more “manly?” The Hollywood myth of Davy Crockett fending off a snarling bear armed only with a Bowie knife does not apply here. Trophy hunters typically shoot bears using high-powered rifles and 8X scopes from at least 100 yards away, while the bear is happily munching on a pile of stale Krispy Kreme doughnuts left at a bait station by their hunting guide (perfectly legal in Alaska). No guide wants his deep-pocketed client to go back home disappointed and empty-handed.

What if you unexpectedly encounter a bear in the wild? What do you do? The answer can be complicated, as the author makes clear. It depends on what species of bear you encounter and on what it is doing at the time. Much of the advice out there is simply wrong.

Advice #1: Drop your backpack and run away. The bear will be distracted by the food in the backpack, allowing you to make your escape. Analysis: Bad plan. This is a great way to train bears to threaten people. Alaskan bears have learned to make mock charges at salmon fishermen, knowing that they’ll run away and abandon their coolers full of fish for them to eat.

Advice # 2: Lie down, curl up, and play dead. Analysis: Bad plan. This might work for grizzlies, who attack only when they feel threatened. Just hope that the grizzly doesn’t decide to make sure that you’re dead. In contrast, black bears regard anyone playing dead as an easy opportunity for a meal.

Advice # 3: If you see a black bear, stand tall, spread out your coat or jacket, try to look larger, speak loudly, or bang pots together to make a racket. If you have a companion, stand close together to look larger to the bear. Back up slowly. Do not turn and run away. Analysis: Good plan. Black bears are great bluffers. They are prone to make mock charges, and to snort and stamp the ground to try to get you to leave their space. They rarely attack. On the other hand, if a black bear is creeping up on you from behind, in total silence, staring intently, you are now on the menu. Be prepared for the worst.

Advice # 4: Carry a gun or a can of bear spray. Analysis: A toss-up. Statistics show that people who carry guns are just as likely to get killed or injured as those who carry bear spray, and people who fail to discharge either weapon are no more likely to get killed or injured than those that do. In the panic of the moment, people either can’t find the can, or fail to disengage the safety on the gun, or just plain miss the target.

Bottom line: Far more Alaskans have been killed by domestic dogs and moose than by bears. Park rangers swear that preventing human/bear conflicts is more about controlling human behavior than bear behavior. People are careless with food and garbage; they assume that bears enjoy posing with you in a selfie; or they approach those cute bear cubs while mamma bear is standing there, watching.

A sad chapter of the book recounts the plight of the polar bear. Polar bears that once swam 25 miles to reach the southern end of the Arctic ice pack now have to swim 150 miles and more to reach their summer feeding grounds. They arrive exhausted and emaciated. The entire population is slowly starving to death. A few more decades of climate change, and the only surviving polar bears will be in zoos. By Pat Biliter, former Burroughs Nature Club vice-president, pbiliter@hotmail.com

*****

2022 January Selection: Sprout Lands by William Bryant Logan

Sprout Lands by William Bryant Logan, a best-selling author, expert gardener, certified arborist, and award-winning horticulturist on the faculty of the New York Botanical Garden.

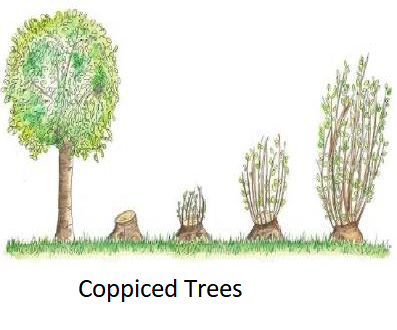

No one would have guessed that a book about the largely forgotten art of pollarding trees would win a Burroughs Medal for the best natural history writing of 2021. After all, how could pruning trees have anything to do with conservation, biodiversity, and ecology?

Around 90,000 years ago (yes, that’s the correct number of zeros) our Paleolithic human ancestors learned how to sustainably harvest wood from surrounding forests, but without killing any trees, a lesson that we modern humans have all but forgotten. By skillfully using tools and fire, they were the first humans to create a renewable resource. No one will ever know who first discovered that trees can be coppiced and pollarded, but archeologists have uncovered evidence of pollarding among prehistoric inhabitants of California, Britain, Japan, Norway, Morocco, France, Afghanistan, Bulgaria, Sierra Leone, and Spain, to mention a few locations.

Pollarding and coppicing is done by removing branches at the top or the base of a tree to encourage regrowth, taking advantage of the 400 million years in which plants have learned to heal themselves from disease and attack.

How does it work? The secret lies in the cambium, the thin layer of living tissue under the bark of all trees. Given the right stimulation, the cambium can re-generate any part of the tree, including leaves, twigs, branches, and even roots.

Insert a freshly cut, bare willow stick into the ground, and it will be stimulated to grow roots, followed by leaves, stems and branches, i.e., a new tree (a clone of the original) without the need for pollination or seeds. This ability gives many types of trees a theoretical shot at immortality, especially when assisted, sustained, and carefully managed by humans.

Although trees live in forests, there is a potential forest in every tree. Every new stem growing on a tree attaches itself to the limb or trunk in the same way that the parent plant sprouted from the soil. Look closely at the base of a large limb on a mature tree, and you’ll see that it attaches itself to the trunk with fingers of tissue that closely resemble roots.

William Bryant Logan

Linden tree at Westonbirt, Great Britain, coppiced and harvested for straight poles, every 10 years or so, for 2,000 years. The original trunk was at the center of the ring.

Pollarded trees

Coppiced trees

If a branch gets damaged, the rest of the tree will not come to its aide. Instead, the branch might save itself by enlisting dormant embryonic buds on the top side of the bark, buds that will grow only in case of need. This is the great biological innovation of shrubs and trees; they secretly store spare parts within their bark. We like to think of tree branches as essential organs for the tree, but in reality they act more like independently competing individuals.

The sprouts, twigs and limbs that grew back were used for firewood, charcoal, boat frames, fence posts, fiber, rope, bridge timbers, poles, tool handles, fish traps, wattle, stakes, woven baskets, construction material, and livestock fodder (leaves and twigs contain more sugar, more protein, and more vitamin B₁₂ than hay). Our Neolithic ancestors harvested the same trees, again and again, for centuries. The practice continued in Europe right up until the late 1800s

By the early 20th century, the art of pollarding had almost been forgotten, especially in tree-rich America. Despite being a professional arborist, the author couldn’t find any old-timers who could remember even “older-timers” who understood the skills and techniques involved. The author had to travel to England, Spain, Norway, and Japan to seek out people experienced in a lost art.

Whole forests have been coppiced and pollarded, but never all at once. The harvesting takes place in sections, separated by four-to-twenty-year increments. The result is a synthetic woodland ecosystem in numerous stages of growth, home to far more species of plants, insects, birds and other creatures than an untouched woodland could support.

Over the millennia, humans learned that the secret to pollarding is to be patient, and not to be greedy. Don’t take too much, too often. Know what to cut, when to stop, and how long to wait. Allow the tree time to recover. Doing so creates an indefinitely renewable source of wood for human use without harming—and in many cases actually enhancing--forest biodiversity.

Therein lies the problem for us modern humans. We want it all; we want it now. The notion of waiting five or ten years for something to come to fruition, much less passing on an agricultural project from one generation to the next, is totally alien to our modern lifestyles. Today it’s all about time (i.e., money). Or better yet, we can simply make everything we need out of non-degradable plastics.

Having observed evidence of pollarding in several foreign countries, I never understood the significance of what I was seeing. To my thinking, the trees were a grotesque parody on Mother Nature, created by out-of-control people wielding loppers and bow saws. This remarkable book proves how totally wrong I was in my thinking. It turned everything I thought I knew about biodiversity, conservation, and edge effects completely on its head. By Pat Biliter, former BNC Vice President, pbiliter@hotmail.com

Urban plane tree pollards on a London street

Beech forest near London that was pollarded for at least five centuries

*****

2021 December Selection: Saving Jemima, Life and Love with a Hard-luck Jay, by Julie Zickefoose

And a book that richly deserves to win the Burroughs Medal, but did not (at least, not yet), is …….

Saving Jemima, Life and Love with a Hard-luck Jay, by Julie Zickefoose, acclaimed artist, author, biologist, Blue Jay aficionado, and a former speaker (2017) at the Burroughs Nature Club. She graduated from Harvard University with a triple major in art, anthropology, and biology. Her greatest joy in life, after her son and daughter, are birds, especially baby birds, with Blue Jays at the top of her list of favorite species.

Many of her artistic subjects were visitors to her 80-acre farm and nature sanctuary in southern Ohio, an ideal place to observe, photograph, and paint wildlife, as well as a place for saving the lives of injured or abandoned baby birds. A licensed Ohio rehabilitator, the author is one of few people in the U.S. who has successfully raised 20 different species of baby birds, each of which presented unique needs and challenges.

Jemima, the “Hard-luck Jay” was found in the middle of a street, where it had sat for many hours, with no parents or nest in sight. Just a few days old, the nestling was in such terrible condition--- injured, diseased, dehydrated and starving---that the author decided not to risk the 2 ½-hour drive to the Ohio Wildlife Center in Columbus. She decided to try to resuscitate and hand-raise the tiny, scruffy, pathetic-looking creature at home. This was her first attempt at rehabilitating a member of the family Corvidae (crows and jays), famous for their keen avian intelligence.

And she succeeded. Jemima grew to healthy adulthood, unrestrained inside the author’s home. It was never confined to a box or a cage. Free to fly from room to room, it even learned how to negotiate the staircase, and quickly claimed all the windowsills that offered the best viewing of wild birds in the yard. Jemima had her favorite perches on the furniture, as well as her preferred spots to poop (newspaper was placed under these). The author notes that a kitchen with a baby Blue Jay perched on the back of a chair suddenly becomes a different place.

The family gave the bird constant attention and indulged it in every conceivable way, spoiling it rotten in the process. For example, Jemima’s typical breakfast included tender white mealworms, chopped strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, sweet corn, mulberries and cornbread. Almost everything eaten by the family was also offered to the bird, in keeping with its omnivorous nature. Jemima picked and chose what she wanted, spit out what she didn’t like, and hid her favorite foods, like watermelon, between the couch cushions.

As the bird got older, the author experimented with an outdoor flight tent, equipped with a perch and plenty of food and water, a safe and cozy place where Jemima could hear other birds in the yard. The experiment was a complete failure; Jemima hated the flight tent. The bird grew despondent, stopped flying, and refused to eat or drink. She recovered only after being brought back into the house with her “family.” Like all members of the crow and jay family, Blue Jays are highly social. They need and thrive on companionship.

Julie Zickefoose and Jemima

Jemima adored the author’s daughter and son. She also loved to land and perch on top of the author’s husband’s head. But the Blue Jay’s favorite family member--by far--was the dog, a Boston terrier name Chet Baker. She would try to get his attention by displaying female solicitation behavior, by teasing it incessantly, by pulling at its hair, and by nipping at its ears and toes. It was a Blue Jay’s way of saying “I love you,” but the feeling was anything but mutual. Trained by the author never to harm birds, the dog had little choice but to endure nonstop annoyances from Jemima.

Strangely enough, Jemima’s relationship with Julie Zickefoose was more guarded, even though the author adored the bird, and even though she had literally saved Jemima’s life from disease or injury on at least three different occasions. To the Blue Jay, the author was the disciplinarian, the one who gave it medicine, the one who force-fed it when it was too weak to eat, the one who confined it (temporarily) to the flight tent to give the poor family dog a break from ceaseless harassment. Blue Jays (and birds in general) are not big fans of discipline. Sadly, Julie Zickefoose could never be Jemima’s favorite human.

Even after the bird was released outside, free to fly away, Jemima chose a “soft release” for herself. She stayed close to the house and continued to interact with the family. During thunderstorms, the bird begged to be let back inside. Another one of her favorite activities was gardening with the family, where her job was to snag grubs, earthworms, and any pillbugs turned over by a trowel.

Bit by bit, Jemima stopped using the house as her primary source of food, shelter, and companionship. Having made friends with a wild Blue Jay, she began disappearing for longer and longer periods. Finally, she left for good, probably with a flock of Blue Jays. The author was deeply saddened by Jemima’s departure, even though her release had been planned all along.

The reasons are sad and tragic. While engrossed in saving Jemima’s life, the author endured a quick succession of heart-breaking personal traumas: (1) her daughter left home for college, leaving a huge void in her mother’s life, (2) the beloved family dog, Chet Baker, died after 12 happy years with the family, (3) her husband of 24 years suddenly left the author for another woman, yielding to a long-time love affair, and (4) shortly after moving in with the other woman, the author’s husband, one of America’s most popular authors on birding, contracted cancer and died within a few months.

The author describes these heart-breaking events without a trace of self-pity or bitterness, only sadness. She believes that her total devotion to saving Jemima kept her rooted in reality, and sustained her hope for the future. This book could just as easily have been called “Saving Julie,” instead of “Saving Jemima,” because it richly illustrates the deep bonds that can form between humans and animals. The author proves how animals enrich our lives in so many ways.

Having read her book, I’ll never see nor hear Blue Jays in the same way again.

Many of her artistic subjects were visitors to her 80-acre farm and nature sanctuary in southern Ohio, an ideal place to observe, photograph, and paint wildlife, as well as a place for saving the lives of injured or abandoned baby birds. A licensed Ohio rehabilitator, the author is one of few people in the U.S. who has successfully raised 20 different species of baby birds, each of which presented unique needs and challenges.

Jemima, the “Hard-luck Jay” was found in the middle of a street, where it had sat for many hours, with no parents or nest in sight. Just a few days old, the nestling was in such terrible condition--- injured, diseased, dehydrated and starving---that the author decided not to risk the 2 ½-hour drive to the Ohio Wildlife Center in Columbus. She decided to try to resuscitate and hand-raise the tiny, scruffy, pathetic-looking creature at home. This was her first attempt at rehabilitating a member of the family Corvidae (crows and jays), famous for their keen avian intelligence.

And she succeeded. Jemima grew to healthy adulthood, unrestrained inside the author’s home. It was never confined to a box or a cage. Free to fly from room to room, it even learned how to negotiate the staircase, and quickly claimed all the windowsills that offered the best viewing of wild birds in the yard. Jemima had her favorite perches on the furniture, as well as her preferred spots to poop (newspaper was placed under these). The author notes that a kitchen with a baby Blue Jay perched on the back of a chair suddenly becomes a different place.

The family gave the bird constant attention and indulged it in every conceivable way, spoiling it rotten in the process. For example, Jemima’s typical breakfast included tender white mealworms, chopped strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, sweet corn, mulberries and cornbread. Almost everything eaten by the family was also offered to the bird, in keeping with its omnivorous nature. Jemima picked and chose what she wanted, spit out what she didn’t like, and hid her favorite foods, like watermelon, between the couch cushions.

As the bird got older, the author experimented with an outdoor flight tent, equipped with a perch and plenty of food and water, a safe and cozy place where Jemima could hear other birds in the yard. The experiment was a complete failure; Jemima hated the flight tent. The bird grew despondent, stopped flying, and refused to eat or drink. She recovered only after being brought back into the house with her “family.” Like all members of the crow and jay family, Blue Jays are highly social. They need and thrive on companionship.

Julie Zickefoose and Jemima

Jemima adored the author’s daughter and son. She also loved to land and perch on top of the author’s husband’s head. But the Blue Jay’s favorite family member--by far--was the dog, a Boston terrier name Chet Baker. She would try to get his attention by displaying female solicitation behavior, by teasing it incessantly, by pulling at its hair, and by nipping at its ears and toes. It was a Blue Jay’s way of saying “I love you,” but the feeling was anything but mutual. Trained by the author never to harm birds, the dog had little choice but to endure nonstop annoyances from Jemima.

Strangely enough, Jemima’s relationship with Julie Zickefoose was more guarded, even though the author adored the bird, and even though she had literally saved Jemima’s life from disease or injury on at least three different occasions. To the Blue Jay, the author was the disciplinarian, the one who gave it medicine, the one who force-fed it when it was too weak to eat, the one who confined it (temporarily) to the flight tent to give the poor family dog a break from ceaseless harassment. Blue Jays (and birds in general) are not big fans of discipline. Sadly, Julie Zickefoose could never be Jemima’s favorite human.

Even after the bird was released outside, free to fly away, Jemima chose a “soft release” for herself. She stayed close to the house and continued to interact with the family. During thunderstorms, the bird begged to be let back inside. Another one of her favorite activities was gardening with the family, where her job was to snag grubs, earthworms, and any pillbugs turned over by a trowel.

Bit by bit, Jemima stopped using the house as her primary source of food, shelter, and companionship. Having made friends with a wild Blue Jay, she began disappearing for longer and longer periods. Finally, she left for good, probably with a flock of Blue Jays. The author was deeply saddened by Jemima’s departure, even though her release had been planned all along.

The reasons are sad and tragic. While engrossed in saving Jemima’s life, the author endured a quick succession of heart-breaking personal traumas: (1) her daughter left home for college, leaving a huge void in her mother’s life, (2) the beloved family dog, Chet Baker, died after 12 happy years with the family, (3) her husband of 24 years suddenly left the author for another woman, yielding to a long-time love affair, and (4) shortly after moving in with the other woman, the author’s husband, one of America’s most popular authors on birding, contracted cancer and died within a few months.

The author describes these heart-breaking events without a trace of self-pity or bitterness, only sadness. She believes that her total devotion to saving Jemima kept her rooted in reality, and sustained her hope for the future. This book could just as easily have been called “Saving Julie,” instead of “Saving Jemima,” because it richly illustrates the deep bonds that can form between humans and animals. The author proves how animals enrich our lives in so many ways.

Having read her book, I’ll never see nor hear Blue Jays in the same way again.